Many years ago I saw LIGHTHOUSE in St Catharines. I am sure i got tickets through the local magazine i wrote for, and recall going down to briefly meet Paul and a few bandmembers after the show. No pics, and I doubt he would recall that. Now, 2025 and I am very happy with this reissue package of the band’s classic Canadian rock album One Fine Morning. I interviewed Paul a couple of weeks back to talk about that era, and more about Lighthouse. Paul talks about the band’s early days leading up to their breakthrough album, working with legendary producer Jimmy Ienner, as well as a few of the band’s hits, Bob McBride, the album artwork, and the band’s current happenings. Lighthouse returns to St Catharines in April. The band also plays Guelph in February, and Pickering (w/ Five Man Electrical Band).

I want to start by talking about One Fine Morning. That was the band’s fourth album. I just want to ask you what kind of led up to that album because you guys had gone through some changes. You changed record labels and you added Bob McBride and things suddenly picked up with that album.

When Lighthouse first started, we had a kind of a fairy tale kind of a story about how to start a band and how to get a record deal. Skip and I met in New York City and I had a play running on Broadway for about six months and Skip was performing at the Electric Circus with his band, The Paupers.

And I just happened to go into the Electric Circus one evening and this Canadian band was playing there. At the intermission Skip came over, recognized me, and said, You’re Paul Hoffert from Toronto. And I said, Oh my goodness, how would you even know that? We’re here in Manhattan, and so on and so forth.

And he said, Oh, well, I’m a rock and roll drummer, but I really like jazz and I always go down to the jazz clubs where you play. So I know who you are, and this and that. We just chatted for a few minutes and then he had to go back on stage.

The next day, what are the chances that I take an Air Canada flight and sitting next to me is Skip Prokop, going back to Toronto. So we chatted, and got a chance to fill each other in on what our passions were personally and musically. And it turns out that both of us love film scores. Skip liked the really big Westerns where the horses would come over the horizon, you hear the French horn and the string sections. And I had scored two movies already and one of them won a prize at the Cannes Film Festival. So I was, you know, on a course towards becoming a film composer at that point.

Anyway, Skip said, Oh, that’s really interesting, because the night I saw him before, the night before was his last night with the Paupers. Skip was managed by Albert Grossman, who at the time, was without a doubt the most sort of famous rock and roll manager, managing everyone from Bob Dylan to Peter, Paul and Mary to Janis Joplin, for example.

And his manager, Albert, had asked Skip to put together a new band for Janis Joplin because a record company deemed that her band, which was fine for getting her career started, was not good enough to do recordings because Janis Joplin had started out as Janis Joplin. And then she became JANIS JOPLIN, and a whole different kind of requirement was needed for the quality of her band. So, Skip had been in discussion with Janis about how to make her band more higher quality. And he identified the weak link, as did many of the reviewers, as the guitar player. So, when he mentioned this to Janis that he planned to bring in another guitar player, Janis was very resistant. The two main problems that Janis had was, number one – the guitar player was her boyfriend; and number two – the guitar player was her drug dealer! So that was a problem. Skip mentioned this to me and he said, I don’t know if this is going to work out. But he said, I’m glad we met because I have this other idea. I love, film music. And he said, you know the Beatles!? And I said, yeah, everybody knows the Beatles. He said, Well, they can’t tour anymore because George Martin, their producer, is recording piccolo trumpets and string quartets and orchestras and all of these things. And then they’re no longer the Fab Four – they’re the Fab Four, plus hundreds of studio musicians, and all this stuff.

And it’s not economically feasible for them to reproduce that on the road. But I’ve been thinking, Wouldn’t it be great to have a rock and roll band that had orchestral resources like strings and horns, and that sort of thing, that could record with all of those instruments and then could go out and perform exactly what was on the record live!? And I said, Yeah, that’s exciting. Skip knew I was an arranger and an orchestrator. He said, Maybe we should do this together because I know all the rock and roll people. I know the record companies. I know the manager, my manager’s, Albert Grossman and so on, and, all about how to, you know, write music and do arrangements and so on and so forth. And maybe we could do it. He said, Now that things aren’t working with Janis, Would you consider putting together a new band with me? And I said, Well, let me think about it. I’ll speak with my wife. I was married to Brenda Hoffert (still), and we had a couple of little kids. I said, OK, let me get back to you. I got back to Skip a couple of weeks later, and I said, Yeah, but I don’t know anything about the music business. I don’t know how do you put together a band, how do you get a record deal…These are things that you have to bring to the table. And Skip said, Of course, I know about all that stuff. So I said, so what do you do? How do you get a record deal? And he said, Oh, we have to write some songs. I said, OK, we have to do a demo. right !? So, Skip came over to my house; we wrote four songs. We went into a recording studio and we recorded those four songs as a demo. And we took them down to New York. The next morning, Skip called his record company at the time, Verve MGM Records, and asked to speak to the artist and repertoire guy, (A&R people, I used to call it. I don’t think they did). At 10 o’clock in the morning, we called and Skip said, can we come down? We have a demo tape. Can we leave it with you? We hope that you’ll listen to it. And I have a new partner and yada, yada, yada. And they said, Sure, come down in about an hour. So, at 11 o’clock, we went to the record company and we anticipated what would have happened in those days and what might even happen today, which was you would hand your demo tape to a receptionist or somebody. And then if you were really lucky, they might forward it to somebody else who might listen to it. But that didn’t happen to us. What happened was the A&R guy said, come into the listening room. I’ll listen to it. He said, how many songs we have? We said four songs. He said, that’s great. It’s not too long. So, we listened to the demo.

They paused for a minute, and he said, I get it. I know what you guys are trying to do. And we thought he got the thing about the Beatles and we could have a band and we could go and do that. But you guys probably know that the record business for the last couple of decades has been earning all this money by the big band era – Frank Sinatra, Duke Ellington, all the big bands of various kinds. And he said, What happens is the students that go to all the high schools and colleges and play in the marching bands and the stage bands take lessons at school and they learn how to play trumpets and trombones and string instruments and all that kind of stuff. And then we sell print music of all the arrangements that are on the big band records and the schools all play them and we close that loop where the schools are doing that and it’s a very good business model. But now there’s this thing called rock and roll and rock and roll is just like drums and guitars.

And nobody can figure out like how you can’t go to the schools and say, you know, here’s an arrangement of, you know, what I’m talking about. So they said, you guys have figured that out because you figured out how to take the rock and roll thing that’s happening and get all those kids who can listen to the stuff that, like on your demo, that has a string quartet and a quartet of horns and a rock and roll rhythm section and do that. So, he said, really, I enjoyed your stuff. Why don’t you go and have lunch?! And when you come back, I’ll have played your demo for some of my colleagues, and depending on what they say, we’ll talk further or not. When we had lunch, we came back at one o’clock the same day that we had called to ask if we could bring our demo down.

They brought us into the conference room and in the conference room was the president of the record company, the vice president of finance. A whole bunch of other people that used to work at all kind of companies called stenographers and secretaries before computers who could actually, would have to, you could dictate contracts and stuff and then they would type them out and then actually, print it out and then you’d have a contract. They said, we want to sign you guys. We’ve talked about it. We think you’re perfect for the label. And we’re willing to give you a really great contract. But we understand that we’re the first label that you’ve shown the stuff to. And we’re concerned that you’ll start shopping it around to different labels and maybe one of the other labels can outbid us or something. So we’re going to make you an offer – If you’re willing to sign a record deal today, we’ll draft it. We’ll give each of you (Skip and myself), we’ll give you a total of 30,000 bucks, 15,000 bucks each, just as a signing incentive. (Well, $30,000 then was worth 250,000 bucks. So, we got the equivalent). Well, a pile of money and we’ll fly your band. Didn’t have a name yet, but we’ll fly your band down to New York. We’ll record you at Electric Ladyland. We’ll spend a ton of money breaking you so that we’ll support you in this and that. And that’s it. But you want some time to think it over. We can only give you a half hour. And if you want to do the deal, we’ll start drafting the contracts. By the time you leave here at five or six o’clock in the afternoon, you can sign the contracts, and we’ll have the checks drawn. You can walk out with a bunch of money and we can move forward. And if you don’t decide to do that, then we withdraw the offer because we don’t want to get him in…whatever. That was the offer. So, they left the room, and I looked at Skip and he looked at me and, we basically didn’t have to say anything. It was basically, what the fuck!? I mean, we’re not going to do this deal? So, we did the deal. So then we had that.

And I was sort of, floating on a cloud because I missed the opportunity to write some songs for a demo. And this band thing that Skip and I had talked about and we had a record deal.

I said, OK, now that we have a record deal, what do we do? And he said, Oh, we need a manager because we need to play gigs. Tomorrow we’ll go see Albert Grossman, my manager, and he’ll be happy that we already have a record deal because that’s one of the hardest things for a manager to do is get the record deal. The next day we went to see Albert Grossman and we offered him the management of Lighthouse, and Albert, unfortunately, thought that our idea was a terrible idea. And he said, Absolutely not. I just put together a band called the Electric Flag, and that’s a nine-piece sort of horn blues band. We just came from our first tour and I lost $110,000 because there’s too many people across this. It’s just really a bad idea. And I basically came back and said, No more bands with more than five people.

So, OK, so I was on a high and then we’re on a low. Now, Albert Grossman didn’t want to manage us. As we’re walking out of Albert Grossman’s office, we meet this guy, Vinnie Fusco, who Skip knew because he was actually an accountant and he managed Albert’s office. He said to Skip, What’s going on? And Skip said, Oh, this is my new partner, and we put together this band. We have this great idea. We brought it to Albert to manage us, but he turned us down. And he said, What’s the idea? We explained to him what we had explained to others. And he said, he said, I think Albert’s really wrong on this one. He said, This is a fantastic idea! He said, I’ll manage you. He said, you think that Albert Grossman comes into the office in the morning and calls out to agents to try to get gigs for Janis Joplin and all those things. I get to the office in the morning and I say, hello, is Vinnie Fusco at the Albert Grossman agency? And I do all of the grunt work. And then Albert signs the contracts. So, he said, I’ll manage you. And he said, It won’t make any difference. I’ll just pick up the phone and say, is Vinnie Fusco from the Albert Grossman agency? So we agreed to have Vinnie Fusco manage us.

We started recording our first Lighthouse album. And what happened was that every day that we were recording, Vinnie would start bringing in record executives from the other record companies and just take a little break and press the button in the studio. And we come in and he’d say, Oh, this is so-and-so from Columbia Records. And then next day, this is so-and-so from Warner Records. Then I think (maybe) the third record company was RCA Victor. And in fact, what Jimmy had doing was he was shopping the band that we had already signed and already gotten the checks and already told our wives we were going to buy houses. The money was already notionally spent.

And they said the deal is all set. RCA is going to take over everything. They know about MGM. They’re going to buy out MGM. They’ll pay MGM whatever MGM had laid out so far. And they’re going to give them some percentage points. You guys don’t have to worry about it. It’s not your money. And now it’s a million-dollar deal that RCA came up with because he said you guys probably haven’t thought about it, but Albert wasn’t wrong when he said that it cost a fortune to go on the road and tour because you guys are going to have a 13-piece band. And I looked up the technical requirements, and the gigs that you’re going to be playing, a lot of them aren’t going to have recording or mixing consoles with enough inputs to be able to mix the strings and the horns and all of that stuff. So, RCA has agreed to build you a custom sound system with 48 inputs and microphones, buy you a truck, get you the big W bass cabinet so that it’s going to sound fantastic in the audience, and so on and so forth. So that’s how we got started. And along with that, Vinny put a couple of extra things in the recording contract that we didn’t have with the MGM contract. Number one, RCA Victor guaranteed that our first concert in the United States would be a sold-out concert at Carnegie Hall, and that Skip and I would have 100% creative freedom to produce the records and do whatever the heck we wanted. And we didn’t have to deal with the label – no suits, no skirts coming up to do that. So that’s what we did.

The very first concert that we did was in Canada, and RCA sent us a New York promo guy, and our first concert was at a place called The Rock Pile. It was a rock and roll club in the Masonic Temple, at the corner of Davenport and Yonge. And somehow, this New York promo guy had gotten in touch with Duke Ellington, who was performing in Toronto, and got Duke to come to introduce our band now with the name Lighthouse at our very first international gig, first Canadian gig. He had all these photographers and television station camera people there, and Duke Ellington showed up and got in front of the thing, and he said, I’m sure you know me, I’ve had a wonderful career with the jazz big-band era. And he said, now there’s this whole new thing called rock and roll, and my new friends Skip and Paul have figured out how to put a band together that’s a rock and roll big band instead of a jazz big band. And he said, I love the idea, maybe this is going to be the next thing in music, I’m beginning to see the ‘Lighthouse’, and everybody clicked the things, and the next day there was stuff in all the newspapers. And then a couple of weeks later, we had our Carnegie Hall concert in New York, which was sold out because RCA just bought billboards on Times Square and they spent money. And right after that, Lighthouse went on the road, and in the first couple of years, we played over a thousand gigs.

We had to work all the time because it was very expensive. So, back to your question, how come One Fine Morning was the first record. The first three records that Skip and I produced where we had creative freedom, we did the kind of music that had no name at that time. A year or two later, they were calling it things like prog rock and fusion jazz, where you were smashing together more sophisticated, more instrumental kind of stuff. But when we put out the first three albums on RCA, AM radios were being installed in automobiles. but no FM radios. And the kind of music that we were playing, the shortest songs were four or five minutes, and sometimes they would go on for 10 or 15 minutes. We didn’t fit the format of AM radio. And so, although we were very popular touring, because in those days it was all the festivals and a lot of the big acts, if you think of Joni Mitchell or Dylan and those people, they may be playing a guitar or a keyboard and maybe a couple of other instruments. But Lighthouse came and when 20 or 30 or 40,000 young people would show up at a festival, we’d fill the stage. So, we were very popular and had very good reviews of our show. But we didn’t get any AM airplay. And so, after the first three albums, RCA dumped us. And they said, It’s too expensive. We’ve really blown a lot of money. They sent us to Japan, where we had a number one hit. They sent us to the Isle of Wight in England, where we won the battle of the big rock bands between Chicago, Blood, Sweat & Tears and Lighthouse. That was a big thing.

And then we couldn’t get a record deal because all the record companies said what Albert Grossman said. It’s a bad idea financially. It cost too much money. And although we’d sold thousands of records, we weren’t selling yet millions of records because we had no airplay on hit radio. So, we looked around for an outside producer who might be able to zig and zag our creative direction, because although the guys in the band were not interested in selling out and doing what the man wanted us to do, which was change our direction and become a hit top 40 band, Skip and I realized that we had to either disband the idea, because we couldn’t exist without a record company to support us, or we had to make a change. And so we brought in Jimmy Ienner, who basically went to our live concert, had a talk with everybody in the band and said he’d be willing to produce us, only under the condition that he had total control over picking the material and that he would try to educate us as to how to write radio-friendly songs, basically two and a half to three and a half minutes long; No big intros, no long outros, no long solos, and things that could get airplay. And we agreed.

So the result of that album was also that Jimmy said, You need to get a really good lead singer also. And Skip had originally said to me, when we were putting the band together, he said, we want to have four horns, four strings, four rhythm sections, and a lead singer. He said, the only thing I wanted to talk to you about was you don’t want to, we don’t want to get a really good singer.

And I said, what do you mean? We don’t want to get a really good singer. He said, look, I’ve been playing in rock and roll bands, if you have a really good singer, they get all the chicks, they basically get all the reviews…and, you’re just a piano player and I’m just a drummer. And I’ve been through that, done that. So, we got a guy who was an okay singer, really nice guy.

But anyway, by the end of doing three albums, our singer, Pinky Dolvin, wonderful guy and okay singer, who had, unfortunately, was stage fright, standing in front of all of these huge resources behind him, blasting out with trumpets and all of these orchestral things. And he said, I’m really sorry to do this to you, guys. I have to leave. You need to get not only somebody better, but you see, I’m drinking a half a bottle of Newfoundland Screech before every show, because I’m just scared to go out and front such a big band. So that’s when we got Bob McBride, that’s when we got Jimmy Ienner. And after Jimmy tutored everybody in the band on what he needed to make us radio friendly and sell a lot of records, all the guys in the band started writing songs, demo songs for this new fourth album. Which was hopefully going to break that problem for us and greatly expand our audience. And it worked. That’s what happened. Now, we all gave him demos. And I’ll come back to this in a minute.

The main thing is, we put out this album, and it was a hit. And the hit single, the biggest hit single from that album, (it had a few) was the same name as the album, One Fine Morning. And what happened was that it was all working out. We were now headlining because we had hit records on the radio. And half of the demos the guys submitted for the recording; I think there were ten demos, five of them made it on to the final album and five of them were rejected by Jimmy for not fitting what his criteria were, or they weren’t good enough.

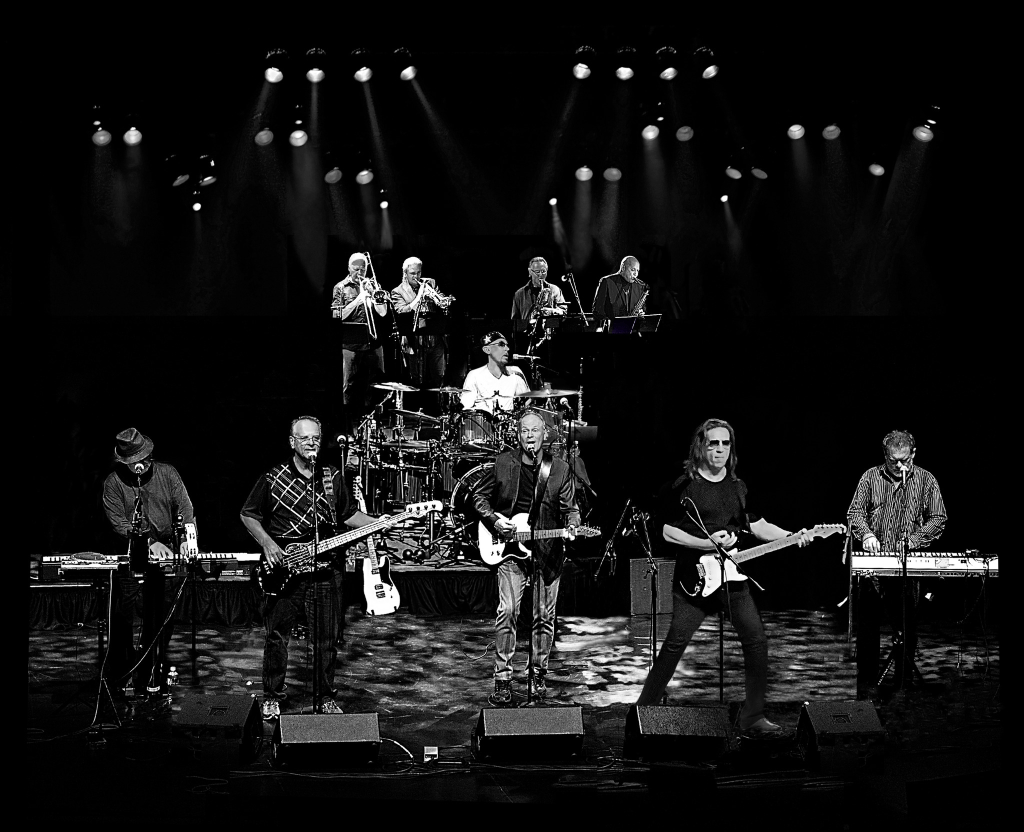

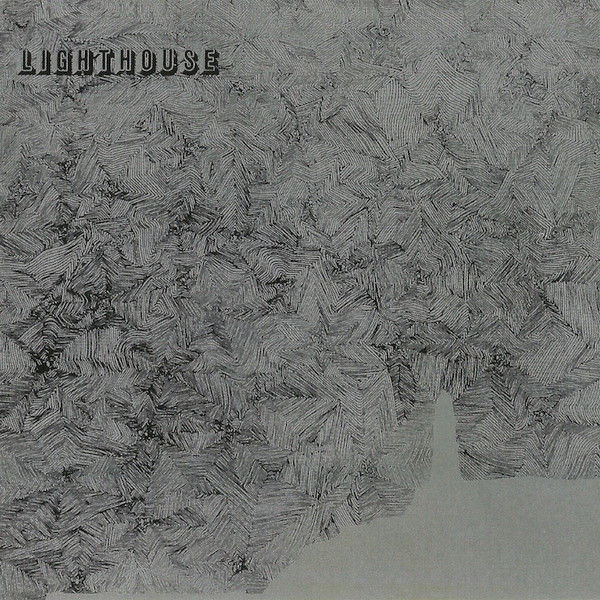

Fast forward half a century, and Lighthouse, against all odds, is still in existence. Some of the original guys – myself, our trombone player, Russ Little, are somehow still in the band. Up until five years ago Skip was still playing drums, he passed away, then Ralph Cole had arthritis, so we had to make a change. But Lighthouse is still able to attract audiences, and it’s wonderful for a guy like me, because I love to perform. So, when we talked to our record company and said We really need to have some new product, because when we play our shows, we usually play twenty to twenty-five tunes, and almost half of the ones that we play are from this one album, One Fine Morning, which was our first big album. This and all these other albums haven’t been available on LP or CD for some thirty – thirty-five years. The record company was very encouraging and said OK how can we figure out a way to start reissuing your classic rock albums, and renew them in some kind of way that it’s not just going to be old news…So we came up with this idea, along with the record company and both the record company and the band were very excited about it. The idea was, that with all the technological advancements that are available now in making recordings available in high-fidelity, we were able to Unmix the original One Fine Morning album. When I say unmix, we were able to take the mixes on that album, and separate them in to a drum track, a guitar track, a vocal track, and all the other tracks, and then we remixed them, raising them up to the super high fidelity of today. And then what we said we’re going to do was take the best performance of the original band, One Fine Morning tapes, and combine it with the best sound you can get today. And we’ll release both double CDs and double LPs. One of the CDs, or LPs, is going to be the One Fine Morning album in the same order as the original 1971 release, and the other album will be all extra stuff that our fans kept on saying We want to know more about not just what you played and why…So, when we went through the archives we found the original ten demos that had been submitted to our producer Jimmy Ienner, five or which made the album, and five of which didn’t. We decided to put in a second disc, and fill it with those demos, and not to remix those because most are just guitar and singer, so they are what they are. So, for those five that made it on to the album, and I’ll just give you an example – “One Fine Morning”, the single that my friend, Skip Prokop wrote, on the demo he sang it because Bob McBride had just joined the band. I think Skip was just playing acoustic guitar, and I was playing conga drums. So, it will give our audiences and fans a chance to hear the evolution of stuff that was submitted. You can see the evolution from one disc to the other where you’d have Bob McBride singing, and there’d be horn and string parts, all of that. And the other thing, that was very exciting for me, personally was Jimmy Ienner was the only guy that ever heard all of the demos, and in order to avoid stirring the pot with all the guys in the band, he chose not to share all of the demos, so that he really on chose what He wanted. So, it was my first time listening to things that hadn’t made it, and the only guys that would’ve heard those were the guys that played on a particular demo. And once we got the idea, that was the start of this new anniversary edition. Both the record company, myself and my bandmates are very enthusiastic about it, because it sounds fantastic. And it’s got all of this new stuff, which is what our audiences keep asking for. Oddly in 1971, the Vietnam war was happening, and in many ways it was quite a bit like the times we’re living in in 2025. Today we have the war in Yugoslavia, a war in Israel, the United States is having almost a revolutionary war. Back then was a similar thing, and bands were trying to write stuff. So, some of the material that we had is very appropriate to the political situations that we have today.

Where did Bob McBride come from, where did you find him?

Bob McBride was a diamond in the rough. He had left home when he was teenager, and started hanging out in what was (and is still) called Yorkville Village, around all of the folk clubs that were there. He had a fantastic voice, but he realized that he needed to get some experience that was at a higher level than he could get in Canada. So he went to Los Angeles, where he hooked up with an incredibly wonderful singer called Johnny Mathis, who had a lot of hit records. And Bob studied with Johnny Mathis for about three months. I think he even lived with him for a bunch of time, during which time Mathis taught him how to breathe and how to do all kinds of really advanced, you know, holding a note forever in through your nose, out through your mouth, and all of that kind of singing technique. And then he came back to Toronto, and when he came back to Toronto, it just happened to be the time that we were auditioning for a new lead singer for the One Fine Morning album. And somebody said, There’s this guy who’s a, he’s a ballad singer. And we said, Oh, I don’t know if that’s what Jimmy is going to want, because we’re doing rock and roll and everything. Anyway, Bob auditioned. And as soon as he started singing, we were just like floored! Skip and I and Ralph (guitar player), heard him sing. And we just said, Oh my goodness, this guy is really fantastic. So, we brought him into the band.

At first, he was suffering from the same stage fright issue that our previous singer, Pinky, was suffering from. That is to say, he had been playing in folk clubs, playing acoustic guitar and singing nice ballads and all that kind of stuff. Pretty stuff. But all of a sudden, out comes Lighthouse with this huge, huge amount of decibels and rock and roll beats. And so I remember the first time he came on stage to sing with us, I don’t remember what the gig was or where it was, but it was somewhere in the United States, and he comes on stage and he’s wearing his acoustic guitar. I walk up to Bob and I say, Why are you wearing your acoustic guitar? He said, Oh, I always wear my guitar when I’m singing. I said, You realize that we’re an electric band, that there’s no microphone on your guitar, there’s no pickup from it; It’s not going to be in the mix in any kind of way. (He says) That doesn’t matter. I just feel more comfortable.

He was hiding sort of behind his guitar, and it took about five or six gigs. But, there’s nothing like a practical experience on stage. And I didn’t know until I started going on stage what it would feel like. And I guess Bob and those other people didn’t know. And there seems to be two kinds of people, there are people who take the nervous energy of being on a stage in front of lots and lots of people and basically it makes them frightened and they don’t thrive with it, and then there are the other guys like Bob McBride and myself who perform a million times better only when there’s an audience and that happens. It turns it, took him maybe a week or two weeks and he just became this unbelievable lead singer who not only sounds fantastic on our albums, but we always, we excited the audience. We’re a very exciting band because we’re very exciting people when we get in front of an audience.

I watched some of the clips of you guys on YouTube. I think there’s one from Massey Hall, and he seemed quite comfortable, quite outgoing, obviously, on stage. I guess you would have never known it at that point.

Oh, yeah. Once we did that, you could see. And if I have the right clip in mind, I’m not sure what the song is that you saw at Massey Hall, but it reminded me of how frenetic I was in those days playing conga drums, acoustic conga drums. It’s always been fantastic for me. It was just an incredibly lucky experience that I did it. Sometimes my colleagues have remarked to me from time to time… that I’ve always felt that getting in front of a live audience, whether you’re an actor in a play or a musician in a band or whatever it is, it’s like jumping off a cliff and hoping that you’re going to have a soft landing.

It’s so different than playing in a recording studio when you’re trying to get everything perfect. What you do when you have a live show, you take all those chances. And sometimes you don’t have a soft landing, but then you have another show the next day. It’s not going out there to everybody else. But yeah, I used to room with Bob and I love him. He’s a lovely, lovely man.

A lot of the songs you guys obviously co-credited in that were on a lot of the songs. Um, can you tell me a bit about how the songs would start? Who would come up with either the lyrical idea or the musical idea? And then kind of what kind of influenced what you guys wrote about on specific songs, like “One Fine Morning” and “Hat’s Off To The Stranger”, those sort of things?

How shall I put this!? From what I’ve heard and seen of The Beatles and some of the other bands at that time, they had a deal and Skip and I had a deal for our co-writing that we would split the writing of tunes and nobody would have to worry about. So, we just said, OK, we’re going to get 50-50 and see how it works out. But every song was different. Certainly in my mind, after Skip took to heart Jimmy Ienner’s instructions about writing radio formatted songs, I just quickly got the highest regard for Skip as a lyricist in particular. Skip and I wrote a few songs that we actually co-wrote. There’s a song on a previous album called “The Chant”, it’s a Buddhist chant. And sometimes one, sometimes the other, sometimes this, sometimes that – but without a doubt, every hit song that Lighthouse has ever had, that’s really gone far on the charts, has a lyric that was written by Skip. And the thing is that, you know, technically I was sort of music director of the band and the bass player used to come with me, and I’d work out the bass parts with him. He actually taught himself how to read music and that happened. And the horn players always needed charts. But, sometimes the string players would write some parts. Sometimes the horn players would write some parts, and sometimes they’d contribute some lyrics. And it would all come out in the wash so that nobody felt that they weren’t being taken care of. Lighthouse was a very collaborative experience. One of our big singles was a song called “Sunny Days” and when I just would read Skip’s lyric for that. Here’s an example…”Sitting stoned alone in my backyard, asking myself, why should I work so hard? Sitting dreaming about the days to come, half undressed, just sitting in the sun”- Beautiful, Fantastic lyric!

And then I would come in and say, Oh, I have an idea for this. I don’t know if it’s going to work. I said that I’ve always been a big fan of Count Basie and his big band. And Count Basie wasn’t the flashy piano player. But I said, Count Basie’s big band jazz always had an acoustic guitar player who would be going chug, chug, a-chug, chug, a-chug, chug, a-chunk... I said, Why don’t we do that, and do it like an old fashioned blues big band…. And why don’t I do like a little Count Basie kind of intro. And with that, then the melodies and all of that stuff started coming together. It’s a simple song. It has some verses; it has some choruses; it has a few chords. And that’s all it is. I don’t think that there’s a uniform way that every song that Lighthouse did was written either by Skip and myself or the other guys in the band. It just happened – Who was where, when, and who had an idea and how did it happen?

I like the demo of with Skip singing (“One Fine Morning”) it kind of reminds me of that Beatles release of Let It Be Naked, where they took all the orchestrations out and it was just the band, the guitars and drums.

Oh yeah. In the demo, we didn’t take anything out. We just, that’s, that was Skip said, I have an idea for a song. And I think, and in that case, Ralph Cole made the guitar part, that was his thing. But basically Skip came up with that idea…he just put a bar-chord down and get that kind of chord that’s not a chord that you can write down in a rock and roll chord. So he starts playing that and I was near a conga drum and we had just played with Santana on the West Coast or something, and we said, Why don’t we do like a Latin-rock thing? And that was a demo…But that’s why I think that this is an interesting kind of package. It’s interesting to me. I hope that others find that interesting as well because people get a chance to kind of listen to it and see how songs evolve, which is different than a kind of Tin Pan Alley, let’s write a hit song kind of thing.

Were you guys, while you were making this album, did you have any sense of when hearing a couple of the songs that it was a step forward, that it was going to be something great?

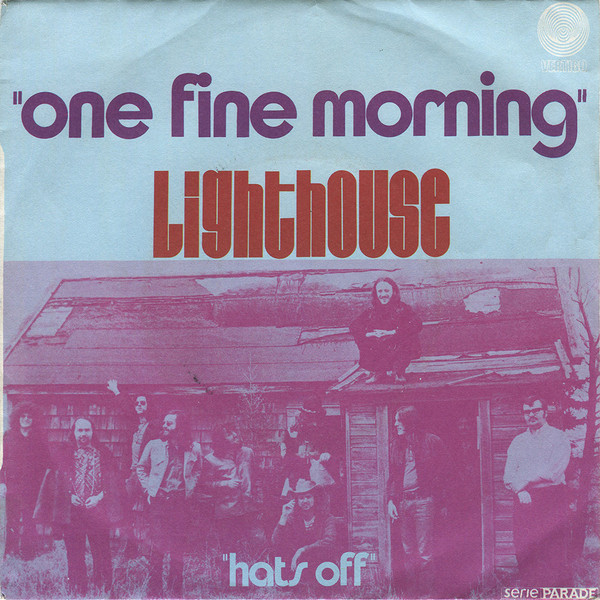

No. And I believe, (and Skip is no longer with us, so I can’t pick up the phone and ask him), but I believe he would agree with me that neither Skip nor I ever had any idea of which songs would become hits. Like “Sunny Days”, that song. Skip and I, it took minutes to, to come up with it. And we thought, Oh, it’s like a novelty song. This will never get on the album probably, but let’s let Jimmy Ienner hear it. And then Jimmy said, and We’ve been talking about it, we want to release that as a single, which was great. And “One Fine Morning”, Jimmy did not want to let us record it because we broke all of his rules. Sometimes you just say, Well, we’re going to do an album, so if you need 10 songs, you want to record like 12 or 13 songs, and then you pick the best 10. So, so we had “One Fine Morning”, and Skip basically insisted, What we’ve got, we’ve got all this energy and everything, you really need to play a jazz piano solo. He says, I’ll take the sound, my drumming way down, and we’ll just sort of do, do, do, do, do, do, do, do…. Now play a nice little thing like that. And I’ll make sure the other guys don’t cover it. We’ll talk to Ralph and we’ll just, do all that stuff. So we did it and we recorded it like that. And, and Jimmy said, Okay, we’ve recorded this, but it’s a six-minute song! I said, We can’t do any long songs. And it started with just bass and drums for 15 seconds. There was an intro to the guitar intro, and that’s all the stuff that Jimmy hated because it just made it not enough hooks, and too much time. Then when it came time to cut stuff in and out of the album, Jimmy played this for the record company people, and they said, It looks like they’re going to, we’re going to put the “One Fine Morning” on the album. And we were really happy, but we knew that it would never be the single. But then we put out the One Fine Morning album and we put “Hats Off To The Stranger” as the first single, a nice structured radio friendly song. And it got into the top 40, which was great for us.

It did the job. And by then this was even just one year later, a lot of the prog rock and FM radios started taking hold. And, the FM stations started playing “One Fine Morning” – the full version! So, if my memory serves me, Jimmy went and cut down the piano solo, cut out the intro and put out the single version of “One Fine Morning” so that we could get AM airplay. And what happened was that we got a little airplay from that. And then all the AM stations just went on the longer version from the album. Could I have predicted that? No. Some people like Carole King (and those people) could just sit down and write songs. I’ve known a lot of great songwriters and I admire them so much. But, in the case of Lighthouse, we could never do it. And we became a lot more successful once we got an outside producer who would start making those decisions, because every single guy in the band would tell us that they knew what would be the single. And then we’d say, Which one do you want? It would always be the song that they had a solo in.

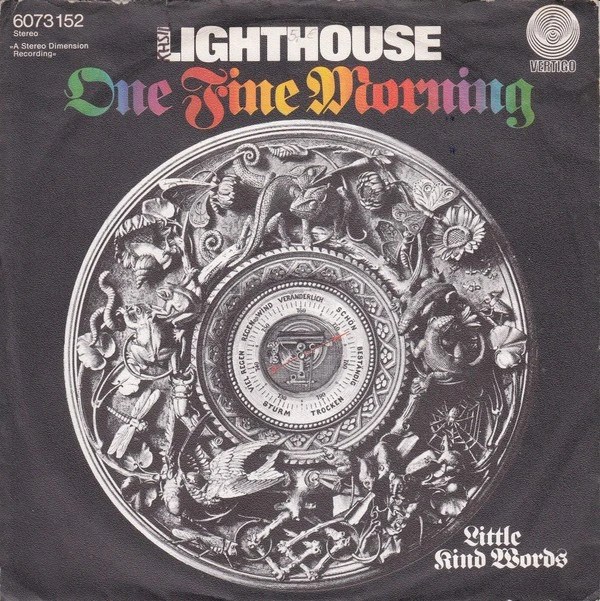

That’s funny. I want to ask about the album artwork. Both One Fine Morning and Thoughts Of Moving On were done by Brad Johansen. And they’re the two in the catalog that are very colorful and kind of stand out. How much input did you guys have in the album art and recall what thought of it and all that time?

The original album artwork for the Lighthouse albums, Skip and I had very little input on it. And some of it we really did not like, we hated the Sunny Days album cover, but the contracts that we had, the record company was always in charge of that. We always felt that they did a bad job, except for One Fine Morning, which was in the middle of the psychedelic era, which we thought that the Brad Johansen cover was maybe the best.

When we went to do this remake, Anthem got a graphic artist to take the original cover and to, I don’t know if you’ve heard the term shiz it up, just pop it out over-saturate the colors… So even what we did, it’s very similar. It’s based on the original artwork.

The other quick little interesting story is when the album came out in Europe, the European record companies…

This was used as the same cover as The Best Of…(I hold up The Best Of Lighthouse LP)

That’s right; the Roger Dean stuff. Roger Dean, who did that, was famous for a lot of things, including that cover. We did a cruise and he had his artwork. This was the original Roger Dean sketch for that fantastic cover. (Paul holds up a sketch of the artwork). And we bought this when we met Roger Dean. You know, if you wanted to buy the original Roger Dean artwork for that record that you showed me, it would probably be, I don’t know, a hundred thousand bucks or more. He’s a very valuable, collectible, artist. But this time around, Brenda Hoffert who manages Lighthouse (my wife), and I were very involved in every detailed aspect of the sound, the cover, the write-up – the guys who had played in the original band, we wanted them to put some text in about how they felt about it, that sort of thing.

How did you guys get hooked up? You were on Anthem originally, right?

So Anthem, of course, was Rush’s record company. And they had all the Rush stuff and I can’t remember exactly when it might’ve been 10 years ago(?) We sold all of the publishing to the Lighthouse catalog of the classic rock years. And we also sold all the master recorders to a company that was then called ‘Olay’.

And Olay, which was financed by the Teachers Union of Ontario or something like that, who had a big wallet to acquire, decided to get a bunch of well-known Canadian music into it’s catalog. So, the word went out that they were interested in, If people wanted to cash out; they were interested in buying copyrights. Brenda and I sold the Lighthouse copyrights and maybe a year later, the guys in Rush sold their catalog to Olay. And then there’s a whole bunch of other Canadian bands that were on Olay. And Olay did some testing and found out that the name Olay, it was a terrible name – Nobody remembered it; nobody could spell it. And they said, Oh, but Anthem’s a good name, so now that we own the Anthem label from Rush, Why don’t we re-brand the entire company, the publishing and the record company as Anthem Entertainment!? That’s where the Anthem name came from. And we loved it because we liked being associated with Rush. We could do a lot worse than that.

There seems to be a great camaraderie of the older bands back in the day; you guys played with like April Wine, Crowbar, A Foot in Coldwater…

Absolutely. Everybody in those days. There was a spirit of trying to do well. Everybody was rooting for everybody else. I think we all, at the time, I don’t remember if they actually use the old metaphor, ‘a rising tide lifts all ships’. We all felt that if we could help any of our fellow Canadians be successful, it’s a success for all of us because that’s what we were really fighting at that time before CanCon.

That’s funny because all those bands that I mentioned were all great at the time. You all had a lot of hit success, but you’re all very different. You couldn’t say there was like two or three bands that were the same or doing the same thing. There’s a big difference between you guys and A Foot Coldwater, April Wine, Rush, and all the various other bands at the time.

Exactly. And, because I had the good fortune to play across the United States, and at the Fillmore West, the Fillmore East and all of those places with all of the acts that had become huge acts over time, but who were coming on. For example, when Lighthouse played in Philadelphia, our opening act was Elton John, because that was his first record and nobody knew who Elton John was. All of that kind of thing that became classic rock. So from Santana on one end to the folk rock of the Grateful Dead. And if you look at the billboards of the acts at the places that we were playing, playing, you’d have like the acts I just mentioned, for example, and then you’d have a rockabilly band with guitar, from kind of fifties and sixties music. It was very diverse and it was very creative, and people listened to the other bands.

I would say that the only act that I ever, consciously, copied a style of piano-playing from was from Elton John, because Elton John, who’s not that well known for this particular thing, figured out something that none of us other keyboard players at the time could figure out, which was how do you take an acoustic piano and make it work with a rock and roll band!? Yeah. It wasn’t easy, but he kind of made it. I can’t imagine that there was any keyboard player at that time that heard what Elton John was doing…We didn’t sit down and say, Aha, now that’s an interesting idea! We didn’t all play like Elton John. We were inspired by each other, but nobody was really trying to cut up the other people or do that kind of thing.

I know this is the first big album for Lighthouse. Is there of a possibility that there’ll be a few more following this?

Yes. It’s all in the works, the question of how many and how soon is something that will depend on how successful this is. I must say that I’ve been blown away. That’s not a term that I use very frequently by the reception, like the reviews that…getting four and a half out of five stars, and just wonderful, nice things that people are saying about the whole process. That could be just a ‘honeymoon effect’ of the album just coming out, and as people are happy about it…We are working hard with the record company to try to make this work for everybody in the audience.

Do you have any desire or intentions of maybe recording any new music with current band?

Of course. We’ve been trying to get record companies to do that for the last 25 years, and none of them are interested. They all tell us that, you know, they do some research, and they basically say, Last year, Elton John released (just to use Elton John as another name, like unbelievably huge star), he dropped two or three singles and we couldn’t get any airplay. The record company would say, We want Elton John, but we want the old stuff!

Do you guys cover the whole catalog in the show or just the hits?

I think right now, the leading plan – the big picture is, we don’t want to go back to the RCA stuff yet because it’s all prog-rock, and we want to build on the hits. So, going from that classic period from One Fine Morning, to Thoughts Of Moving On, to Sunny Days – there was four or five albums, which had a couple of tunes that did very well. I think the ‘loose’ plan is to re-introduce the Lighthouse classic-rock stuff to newer, younger audiences, and each time the extras might be different, but to do that in a way that makes it new albums, at least in a way that’s new – to us (haha). Because a lot of stuff in the archive we haven’t seen. So I’m not giving anything away, because it’s not etched in stone, but I think that’s the general plan, and that’s one of the reasons I’m so happy that the initial reaction has been so strong.

LINKS:

https://www.lighthouserockson.com/

https://www.facebook.com/groups/lighthousetheband